Culture is a marker of humanity’s collective conscience and a tribute to its inventiveness. It is the primary anchor for people and communities to define their identities and experiences of everyday life, particularly in the context of cities where local cultures act as effective resources in encouraging social integration and peace, writes Jitendra Singh Chouhan, Chief Executive Officer, Ujjain Smart City Ltd.

Culture is regarded as the fourth pillar of sustainable development as it contributes transversally to many Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – safe and sustainable cities; decent work and economic growth; reduced inequalities; environmental conservation; gender equality; and peaceful societies. With growing international sensitivity around the topic, cities around the world have started considering cultural heritage management as the nexus for crossdisciplinary inquiries on biodiversity, ecosystem services, and human wellbeing challenges in these changing social, economic, and environmental conditions of today.

In the past, cities have leveraged local cultural resources to inspire, catalyse and drive socio-economic change, and enhance local resiliency and development potential. Nowhere is it more apparent than in India where culture has interfaced with the political economy through its various manifestations of local practices, oral traditions, and cultural expression to influence policy decisions on the local economy or the provision of critical services (water, housing, public transport, etc). But unplanned expansion and construction in the face of rapid urbanisation threaten to derail the historic areas and heritage assets of our cities, and their evolution. Despite wielding a huge influence in the past, the rich heritage legacy of our cities is underutilised in modern infrastructure development. A sector-based approach ignores the cross-cutting benefits that incorporating urban heritage brings to a city’s socio-economic development.

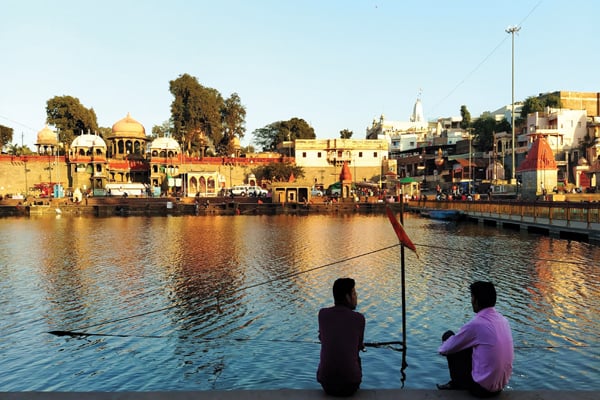

Ram Ghat Showing Ganpteshwar Mahadev, Kashi Vishweshar temples

Legislative frameworks, policies, and programs have traditionally been tailored to different sectors of urban infrastructure, while culture and heritage have been limited to ‘mainstreaming’ efforts. For ensuring sustainable development, it is important to address cultural heritage management as a domain in its own right. ‘Mainstreaming’ should not imply that culture is just a transversal dimension and hence less visible and less present for development projects and in people’s minds.

Urban heritage is understood as the historic layering of values that have been produced by successive and existing cultures in cities. It is an accumulation of traditions and experiences, recognised as such, in their diversity. For such culturally rich cities, it naturally follows that culture must be at the heart of development policies to ensure human-centred, inclusive, and equitable urban development. There are examples from around the world (Matera in Italy; Ouro Preto in Brazil; Ostersund in Sweden; HRIDAY cities in India) where an integrated approach has proven to be successful in provisioning critical infrastructure in those historic areas which generally tend to be overpopulated and under-serviced. It has also led to greater buy-in from the local communities and has proved effective in reducing urban poverty.

Historic Retaining wall near Harsiddhi ki Paal

This is relevant in the case of Ujjain which is one of the oldest cities in the sub-continent. One of the seven janpads of ancient India, there was a time when this city was the capital of a big empire and a central node for land and water trade routes. Enjoying immense political and economic importance, Ujjain served as a centre of science and culture in northern India; for instance, since the fourth century B.C.E., it has served as the first meridian of longitude for Hindu geographers. It is no surprise to find that Ujjain is home to numerous legends of Indian history, such as the stories of Kalidas, Emperor Ashoka, King Vikramaditya, Banbhatta and Varahmir. Ujjain is also very rich in natural resources and biodiversity. There are seven water bodies in the city named as Sapt-Sagar. River Kshipra, which was once majestic and massive, was an important means of trade and transport. The city had huge forests of various indigenous species, housing a plethora of bird populations. Today, Ujjain is a leading heritage city in the country with prominent temples such as the Mahakaleshwar Jyotirlinga and Harsidhhi Shaktipeeth adorning the cityscape. In fact, Ujjain has hundreds of temples, and the sizable economy of the city is directly linked to tourism and trade.

The Mahakaleshwar temple area succinctly captures all the challenges and opportunities of incorporating heritage in urban development. A very densely populated area with old structures, natural resources and high archaeological value, the temple and its surrounding areas need to accommodate the already stretched infrastructure and public management systems for a disproportionately high population during festive days. To put this into context, approximately 75 million pilgrims visited the city within a month during the Kumbh Mela (Simhast) in 2016, i.e., around 2.5 million pilgrim visits per day. Over the years, this overstressing and increasing urbanisation has also had severe impacts on the city’s water bodies.

Also Read: Safeguarding Cultural and Natural Heritage for Sustainable Urban Development

Decision-makers and stakeholders in Ujjain recognised that managing the underlying tangible heritage and the archaeological treasure trove around the temple premises was important, especially when we recollect that the temple (along with the city) was pillaged several times in the past for its riches. Additionally, there was cognisance that the natural heritage of the city, i.e. water bodies, and flora and fauna, were also at risk and needed to be conserved. It was therefore imperative that we considered the redevelopment of the Mahakaleshwar area as the core focus of the city’s efforts in the Smart Cities Mission (SCM) through the MahakalRudrasagar Integrated Development Approach (MRIDA) project. The objective was to sustainably increase the carrying capacity of the area while enhancing the cultural experience of pilgrims and tourists and preserving/ restoring the public spaces and temple precinct. Distributed into three phases, the MRIDA project is a flagship project in the Indian urban domain. The second phase of the project, MRIDA-II, is co-financed by the CITIIS program (funded by AFD and the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs).

CITIIS is a joint program of the Ministry of Housing & Urban Affairs, The French Development Agency (AFD), the European Union and the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA). USCL is one of the twelve cities that won the CITIIS challenge in 2019 and it has been awarded a grant of Rs 80 crore from the Government of India for this project. While efforts were being made under phase 1, it was only under the influence of the program objectives of CITIIS that we were able to thoroughly conceptualise a coherent strategy for Cultural and Heritage Management planning in Ujjain.

The core objective of our planning was to provide adequate civic amenities for the floating population with minimum impact to the riches of the historic town. Integrating culture into local sustainable development contexts adds additional complexities of place and socio-cultural resonance to urban planning. The challenges must be explicitly addressed. Assumptions and prevailing myths about the culture that continue to seep into policy and project discussions stall progress in integrating culture into urban development in more systematic and comprehensive ways. This was the approach undertaken in Ujjain.

We realised that heritage conservation and management must be carried out on a continuous basis, and a comprehensive listing and grading are required to achieve the task of effective conservation. Long-term management of heritage requires a nuanced understanding of measuring and evaluating the impact of cultural policies, plans, and projects. Culture cannot be measured and monitored like other areas of urban development since it has important non-quantifiable and invisible dimensions. To know that culture is contributing to strengthening and enriching local sustainability, resilience, and holistic development, the measurement or assessment criteria must focus on stages of improvement (qualitative criteria) in combination with quantitative criteria.

As part of the CITIIS program, Ujjain Smart City Limited (which is the executing agency for the project) prepared a Cultural and Heritage Management Plan (CHMP) as part of the Environment and Social Management Plan (ESMP) commitments made in relation to the management of cultural and natural heritage during the construction and commissioning phase of the project. This was done in accordance to the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Standards (ESS 8) which form part of the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework.

As a part of the planning process and with the guidance of renowned experts in the field who were part of the Technical Assistance provided by CITIIS, we used the following benchmarks to guide our activities:

● Heritage conservation is best understood as a socio-cultural activity, not simply as a technical practice; it encompasses many activities preceding and following any act of material intervention.

● It is important to consider the contexts of a heritage conservation project—social, cultural, economic, geographical, administrative—as seriously and as deeply as the artefact/site itself is considered.

● The study of values is a useful way of understanding the contexts and sociocultural aspects of heritage conservation.

● Traditional modes of assessing ‘significance’ rely heavily on historical, art historical, and archaeological notions held by professionals, and they are applied basically through undisciplined means.

The CHMP prepared defined the avoidance, minimisation, and mitigation measures necessary to ensure that negative impacts to known and unknown cultural heritage features/sites because of project activities are prevented or, where this is not possible, reduced to as low as reasonably practicable during the execution phase of the project.

View of Ramghat showing iconic Shree Venkteshwar Dharamshala (Bombay wale ki Dharamshala) and Ranoji ki Chhatri by Scindia.

The approach used by USCL considered the relation between tourists and residents, aiming to address it as a relationship rather than focusing on the potential tensions and seeing art as something that can facilitate that relationship, particularly when residents are given a voice as creators. The local or regional tangible and intangible heritage is easy for people to relate to through their own memories. That means that this kind of heritage— especially in the recent past—becomes a very efficient tool when it comes to creating learning experiences that can really reach people in community, culture, and pilgrims.

All aspects of the project were considered and activities were defined during each phase of the project. In all, more than 100 ‘Mitigation Measures’ across 19 ‘Impact Types’ were identified across 48 sites contained within the project boundaries. In complement, a detailed ‘Chance Find’ procedure was established that outlined actions required if previously unknown heritage resources, particularly archaeological resources, are encountered during project construction or operation.

Emphasis was laid on stakeholder consultation and engagement, scholarly research about the site to know of any event or a significant site associated items, detailed survey, and assessment of the site to know of any potential unknown cultural heritage and finally training of the working staff along with a monitoring specialist to make sure no harm is caused to the heritage of the city. In addition to the above, USCL has employed a Conservation Architect (CA), whose responsibilities include:

● Promoting compliances with the Heritage Management Plan and procedures for the project activities.

● Ensuring that all required approvals for archaeological work have been obtained from the appropriate government bodies.

● Coordinating, scheduling, developing the scope of work and supervising the archaeological works of the contractor.

● Verifying and establishing the cultural heritage significance of any finds during the project with help from the third party subject experts or agencies as may be applicable.

● Carrying out cultural heritage training.

● The monitoring of archaeological works, trial trench investigations and rescue excavation work will be the responsibility of the conservation architect

● Undertaking archaeological excavations and investigations.

Also Read: Cultural Heritage for Sustainable Urban Development

By experiencing diverse cultural practices, young people are provided with favourable conditions for a more satisfactory intellectual, emotional, moral, and spiritual existence, having the chance to live, work, explore, communicate, create, and express themselves in unconventional and completely unknown ways. The project s realised in a dialogue between identity and diversity, individual and group contributing to cultural diversity through a common process of shared activities, interactions and exchange between the elderly and the young.

The recognition that heritage relates to the environment and to landscape and that it is conveyed in knowledge, beliefs and values, places heritage in close connection with a wide range of practices and places. This also points to the need to acknowledge the place of heritage in several policy fields and indeed to the policies and strategies that relate to sustainable development at the local, national, regional, and global levels. We, in Ujjain, realise that it is not just the local government that has an integral role to play in holistic heritage conservation, but also citizens, civil society organisations, and heritage professionals, among other stakeholders, that contribute to the prominent role of cultural heritage in society and the economy. To continue to value, protect and preserve it, we must strengthen the existing links between cultural heritage and sustainable development, and incorporate the appropriate rightsbased, people-centred practices.

Be a part of Elets Collaborative Initiatives. Join Us for Upcoming Events and explore business opportunities. Like us on Facebook , connect with us on LinkedIn and follow us on Twitter, Instagram.