According to a report of the Observer Research Foundation, the water and wastewater sector in India is developing at a rate of 10-12 per cent each year and is likely to exceed $4 billion due to rising demand for water and wastewater treatment plants in the country. There will be a significant investment gap in this industry, which the private sector may cover through technology selection, fund rotation, and execution, writes Rajiv Ranjan Mishra, Chief Technical Advisor, NIUA.

The majority of Indian cities/ towns lack basic sewerage infrastructure, and those that do have partial sewerage systems operate at sub optimal capacities. This leads to discharge of most of the wastewater into water bodies with partial or no treatment, causing serious environmental degradation. In sanitation sector, while much has been achieved for providing access to toilets to all the households, mainly through Swachh Bharat Mission, supported by missions like AMRUT etc., the largest gap remains in the development of sewerage infrastructure with adequate treatment capacity, along with a network to transport wastewater to sewage treatment plants, where treated wastewater can be reused or discharged after adequate treatment, as per stipulated standards. According to the latest report of Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) for 2020-2021, the estimated sewage generation from urban areas is 72,368 MLD, with total treatment capacity from 1,631 STPs (including proposed STPs) being only 36,668 MLD covering all 35 states/UTs. Out of these STPs, 1,093 are functional, 102 non-operational, 274 under construction, and 162 slated for construction. When compared to the previous inventory of STPs (2014), it is discovered that sewage treatment capacity has increased by 50 per cent. The gap in treatment capacity, however, remains enormous, as seen from the above statistics and even out of this existing capacity, the actual capacity utilisation complying with prescribed standards is only 20,235 MLD, and the remaining quantity of 52,133 MLD is let-out as untreated/ improperly treated sewage to water bodies and rivers.

The poor performance of existing service providers in the sector and non- compliant STPs as well as suboptimal capacity utilisation is caused by a combination of improper planning, lack of funds and technical capability, along with traditional lack of attention by decision makers. These factors and the massive investment requirements anticipated in this sector has led to the exploration of Public- Private Partnership (PPP) models in the sector as a panacea for the aforementioned problems. According to a report of the Observer Research Foundation, the water and wastewater sector in India is developing at a rate of 10-12 per cent each year and is likely to exceed $4 billion due to rising demand for water and wastewater treatment plants in the country. There will be a significant investment gap in this industry, which the private sector may cover through technology selection, fund rotation, and execution.

Also Read: Wastewater Management in Urban India

SDG 6.3 aspires to improve water quality, reduce pollution and untreated wastewater load and substantially increase recycled and safe reuse of treated wastewater. This demands substantial investment in new sewerage infrastructure, rehabilitating and upgrading the existing infrastructure, developing and practicing new and suitable technologies and an optimal mix of solutions for centralised as well as on site and in situ treatment, promoting nature-based solutions etc. Long term operation & maintenance (O&M) need to be embedded for sustaining the benefits of capital investment. The huge financial requirements to expeditiously bridge the huge gap between the generation and treatment capacity, while ensuring high quality standards, would require private investment in addition to public funds. Inadequate sanitation leading to huge social and economic costs on account of poor health and hygiene further makes a case for such investment.

The main policy governing the urban sanitation and sewerage sector is the National Urban Sanitation Policy (NUSP) of 2014. This also emphasises on wastewater reuse for conserving water and also improving environmental standards. It is suggested that at least 20 per cent of the generated wastewater be utilised promoting the prospect of income generation from the sale of treated wastewater. It also recognises the role of public-private partnerships (PPPs) in this sector, in terms of investments, cost recovery through wastewater reuse mechanisms, and improved management of sewerage treatment facilities and networks.

PPP models that are in use in wastewater management

Most sewerage projects in India are apparently not financially viable for usual PPP because current user charges do not cover O&M expenses, let alone capital requirements. As a result, commercial financing of these projects, completely through the bank loan or bond markets, is not a viable alternative at present without the adequate backing from government. The majority of sewage projects in the country have been funded by a combination of subsidies from national/state governments and multilateral/bilateral loans guaranteed by the Government of India. The major sources of funding for sewage projects in the government sector include grants from the central government, grants and loans from state governments, loans from multilateral/ bilateral agencies, and taxes and user charges, including one-time connection fees from ULBs.

Alandur, an urban local body in Tamil Nadu, first attempted a PPP initiative in this sector. Between 2000 and 2005, approximately six PPP projects were attempted, including Alandur, Tirupur, and four projects in Chennai. Between 2006 and 2011, the number of PPP projects attempted in the sector expanded due to the availability of financial support from centrally sponsored schemes and several urban missions. A major boost came from the Namami Gange mission which systematically developed PPP through Hybrid Annuity Model for wastewater sector. AMRUT 2.0 and SBM have also incorporated PPP and the national policy level push on PPP in the infrastructure sector has made it percolate to state and city level. Many of them now have projects with PPP initiatives and are gaining experience in the design of concession agreements, balanced risk sharing mechanisms which are essential for the success of PPP projects.

An analysis of these PPP models in India show that the BOT End-User PPP and the DBO model were the two most successful ones. The DBO Model is a success if private operators are given some type of guarantee on O&M payments. However, because the private operator is the end user, the BOT End-User PPP model is successful even without payment assurances.

Another approach to address revenue risk concerns of the private sector and government’s own desire to ensure that the private sector has some “skin in the game” to ensure commitment and performance of private sector over the duration of concession is to combine the BOT Annuity and the DBO models, which is Hybrid Annuity Model (HAM). National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) introduced the HAM model in wastewater management under the Namami Gange Mission. HAM had its origin in the highways sector.

In a funds-stressed situation and lack of sufficient toll income, National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) was exploring alternatives to the conventional Design, Build, Finance, Operate and Transfer (DBFOT) model that relies on Grant/Premium or Annuity modes. NMCG modified the road sector HAM bringing innovative features for building confidence of private players and held extensive market and stakeholder consultations. By now, NMCG has 30 projects with a sanctioned cost of more than Rs 11,000 crore for 1700 MLD new capacity, along with rehabilitation of older assets and O&M for 15 years.

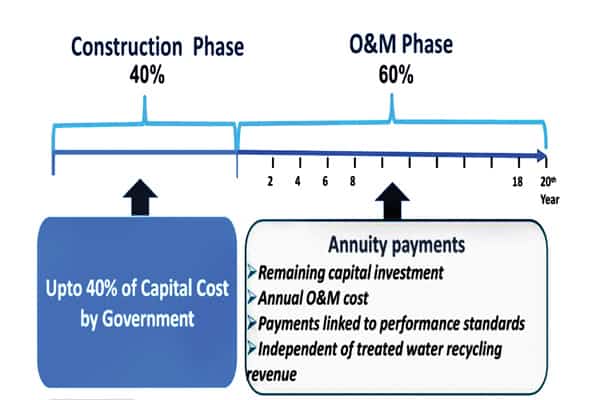

Under the HAM, a significant portion of the capital cost of the project is required to be financed by the private developer. This amount is paid by the government to the developer in equal installments over the term of the concession, subject to sustained performance. 40 per cent of the capital cost for the project is paid by NMCG during the construction period, and balance 60 per cent along with interest paid as quarterly annuity along with Operation & Maintenance (O&M) cost during a period of 15 years.

Overview of HAM Model

This is a paradigm shift from payment for construction to payment for performance. One City-One Operator (OCOP), next innovation was conceptualised and implemented by NMCG for improving citywide governance in wastewater management. OCOP has led to the paradigm shift in managing sewage treatment in a city by integrating the development of new STPs with the existing treatment infrastructure in the city/town, with their rehabilitation/ upgradation as needed and O&M of all assets-new and old for 15 years under HAM, with an aim of achieving “no untreated sewage shall enter in to the river Ganga”. OCOP ensures singular accountability of the entire sewage treatment issue in a city.

With the significant potential for scaling-up, it is important that the perception risk should be mitigated through alternative cost-effective Payment Security mechanisms, which is sustainable, consumes less capital and be more cost effective for the whole program. Wastewater, in many cases, is rich in recoverable materials. This may be the nutrient value of domestic wastewater or indeed a particular fraction of an industrial discharge. In many regions, the use of wastewater in agriculture is well understood, albeit in a way that carries significant health risks and hence, safety standards are important. What is needed is a better matching of available treated wastewater to the different reuse requirements in different purposes such as agriculture, industry, city needs, recharge of water bodies etc.

Also Read: Wastewater management in unauthorised colonies

A national framework for safe reuse of treated wastewater is under development and many states have now come up with state policies. Gujarat and Tamil Nadu have several successful models for such reuse and Surat has significant income out of this. Hyderabad has also taken up major STP projects on HAM. The Mathura sewerage project under Namami Gange is a successful example of integrating the HAM model, OCOP approach and reuse of treated wastewater. successful models for such reuse and Surat has significant income out of this. Hyderabad has also taken up major STP projects on HAM. The Mathura sewerage project under Namami Gange is a successful example of integrating the HAM model, OCOP approach and reuse of treated wastewater.

This project at a cost of Rs 437.95 crore integrates both the construction of new STPs (30 MLD) and rehabilitation & maintenance of existing assets (37 MLD) under one operator for the whole city. This has a capstone component of a 20 MLD Tertiary Treatment Plant (TTP) for reuse of treated wastewater by Mathura Refinery of Indian Oil Corporation Ltd (IOCL) for non-potable purposes. It saves 20 MLD fresh water from Yamuna for the refinery.

In order to ensure quality in delivery of urban wastewater management services, performance based contracting either through HAM or any other PPP mode should be adopted as a matter of policy. This will also support the implementation of polluter pays principle and help in achievement of sustainable development goals in the long run. Sector would flourish, mature in terms of reduced cost of treatment, assured quality of treatment & sustainability once more and more states adopt this approach.

Be a part of Elets Collaborative Initiatives. Join Us for Upcoming Events and explore business opportunities. Like us on Facebook , connect with us on LinkedIn and follow us on Twitter, Instagram.