1. Introduction

As natural resources and readily available, easily transformable energy were the raw materials out of which the Industrial Revolution was forged, so Information and Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs) are the raw materials out of which the Information Revolution is being forged. And just as the Industrial Revolution was transformative of all aspects of daily life including all aspects of economic and social production (and reproduction) so the Information Revolution is similarly transformative.

We can now step back from the Industrial Revolution and see its key elements, its defining moments, the changes that it brought about and the key conditions which made its sweep and power so decisive. Having such a capacity for insight and oversight is however, rather more difficult for the Information Revolution since we are at the moment well into it but by no means has it even begun to run its full course and particularly in Developing Countries.

It is in this context that we must understand the concept and the principles underlying a “Right to Information” (RTI) and both the likely impact of the broad-based introduction of such a right and the manner and type of outcomes which will be its result, particularly as these affect those at the local and grassroots levels.

2. Looking “bottom up” at the Right to Information

The challenge of the “Right to Information” is that while such rights may have been translated into laws, the practice of enforcing such rights is one which in many contexts is out of the reach of those without considerable access to legal or financial resources. And it is those with the least resources who may have the most need to have access to such “information”.

Having a “right to information” makes little sense if “access” to that information is too costly for ordinary citizens to operationalize; or if such “access” is limited only to those who for example, have a high level of literacy skills or advantageous access to computer facilities and the Internet. The exercise of this right may be denied in practice whatever the law if information access is unnecessarily restrictive, too costly or discriminatory as for example, through the absence of information availability in appropriate languages or in the case of those without literacy skills in a format which is accessible to the illiterate. Simply making information “available electronically” or “on the web” may have little effect without a related provision of the means for reasonably available and minimal cost access.

In this context the “Right to Information” can be understood as having two facets from the perspective of the grassroots:

a. access to general information such as the information that governments (and others) make available for example, concerning entitlements and benefits, medical information or information that might be of interest from a working conditions or occupational health and safety perspective among others.

b. access to specific information such as might those concerning individual files, services or entitlements related to individuals, specific decisions made and decision making by government officials and so on.

In both of these instances information technology can play a significant role. In the first instance, by lowering the cost of information access and by facilitating its broadest possible distribution (and potential accessibility) through email or the World Wide Web. In the second instance, by enabling the development and enhanced “transparency” of information records, tabulations, data bases and so on to which ordinary citizens can have ready and low cost access through electronic means . But in order to do so the provision of information has to be understood as something that doesn’t just happen but must be treated as something requiring an approach understood as an “effective use”.

Also, it should be noted that the issue of “digitization of records” is still subject to attitudes critical of computerization among many of those involved in public policy issues – inside governments and outside. In fact, a position critical of new technologies is often seen as being necessary if one is to be understood as being supportive of disadvantaged people. In fact, the (Right to Information) RTI Act is India’s first law that obligates governments to take up e-Governance. Quoting the Act: “Every public authority shall… ensure that all records that are appropriate to be computerised are, within a reasonable time and subject to availability of resources, computerised and connected through a network all over the country on different systems so that access to such records is facilitated. Public and judicial activism can progressively increase the interpretation of all records that are appropriate to be computerised.” In a recent workshop on RTI in Delhi many participants were concerned that too heavy focus on the Internet was not appropriate considering the conditions of rural India today, where connectivity is low.

Effective use and the Right to Information

It should also be noted that a “Right to Information” is meaningless and particularly for those with little means without a consequent means for enabling the “effective use” of this information. In another context, the notion of “effective use” has been developed as an approach to ensuring that access that is made available in attempts for example, to “bridge the Digital Divide” are in fact of value and benefit to the population towards which these applications are addressed. An “effective use” approach would be concerned to ensure that RTI was supported not simply by the means to access the information element but also that it was usable by those making access thus that it is accessible to those with various types of disabilities; designed to be usable given various types of Internet access; available in local languages and supports use by those with little or no literacy skills; downloadable with local means to print in a usable and affordable manner; and perhaps of most importance that there are institutional and organisational structures and supports that enables the translation of “accessed information” into real and valuable use by citizens as for example, in linking the information in public records to the making of formal complaints.

RTI and e-Governance

In India, in particular, there is the additional issue that if the RTI were to be fully executed it is likely that the current governance system would be unable to cope. The scope of this issue is in India enormous and its potential impacts very substantial given the very high cost of servicing even a single request for information. The argument that is frequently made that one successful RTI request obviates the need for many others, as the system perks up and begins to deliver better, may be underestimating the inertia of the system and not recognising the impact of the petty corruption which surrounds information access in India (and in many other developing countries as well).

Digital technologies which provide the means for very low cost publishing and information distribution are quite evidently the necessary supports for the RTI, and without them the promise of any RTI law or similar ascribed right cannot be optimised.

An additional issue with RTI processes where ICTs may have a significant influence is that in many cases when information is requested this request has to be addressed to the very office or official where the information in question may potentially have the most damaging effect. In this instance, the officials in question have the least incentive to disclose and the most incentive (and means) to undertake “damage control” (information access restrictive) measures – a situation where the citizen is necessarily at a significant disadvantage.

The electronic publication of government information could ensure remote access to information without giving a ‘warning’ to the potentially affected officials. Such processes also allow senior officials up to the highest levels to monitor RTI access to government information remotely, once again without any particular office/official to having knowledge that such a monitoring is being done.

The costs of e-Governance, i.e. broadly, digitising records and processes, though expensive, has to be seen in the context of the overall cost of government and particularly for the Indian governments which runs a quite expensive establishment. This establish-ment however is one with low levels of efficiency and high levels of wastage and one, which would almost certainly be very positively impacted through the widespread introduction of ICTs.

Today, even a small office of, say, a grassroots NGO has begun to realise that computer-based office work is more cost effective than manual process – whether it be for accounting, documentation or communication. Governments in developing as in developed countries are simply small offices multiplied into the tens of thousands or even millions where each in turn could benefit from computer applications. When linked together by means of the Internet, these could achieve very significant additional improvements in effectiveness and potentially massive cost and overall efficiency benefits as well; but of course while also taking steps to limit the opportunities for the potentially very significant wastage and corruption leakages that changeovers of this scale can themselves engender and particularly in countries such as India where there are entrenched patterns of corruption.

There is of course the need to build the institutional systems and processes that give body to the provisions of the Act. These processes and systems include institutionalisation of practices of seeking and obtaining information from government bodies and also being able to use this meaningfully. Great vigilance and high level of activism by citizen groups is needed in the initial and potentially protracted period of RTI implementation as practices are established and institutionalised, and where they can be expected to have significant resistance from the bureaucracy. Often this will require working with some supportive bureaucrats to build good working systems of obtaining information through RTI, and using it to enforce accountability and improve public service delivery.

As against getting one-off access to useful information, building working systems over the new legal provisions is more important. Many in the establishment have the good intention to improve governance but are impeded by poor existing systems, and working with them to build new citizen-empowering systems is an important work for citizen groups. Perhaps what is needed as a start is to take a simpler, more home-grown, approach to e-Governance – one where 2-3 years are taken to digitise all processes and documents in one district in a manner that all systems work ideally as per plan (for which will be needed local political and employee level “buy in” including an understanding of what this will mean from personal employment and income perspectives). This being done, the cost saving and output improvements will be easily proven. And since in most cases, governance processes are the same across all the districts within each national grouping, the system can be exported everywhere within the country.

As against getting one-off access to useful information, building working systems over the new legal provisions is more important. Many in the establishment have the good intention to improve governance but are impeded by poor existing systems, and working with them to build new citizen-empowering systems is an important work for citizen groups. Perhaps what is needed as a start is to take a simpler, more home-grown, approach to e-Governance – one where 2-3 years are taken to digitise all processes and documents in one district in a manner that all systems work ideally as per plan (for which will be needed local political and employee level “buy in” including an understanding of what this will mean from personal employment and income perspectives). This being done, the cost saving and output improvements will be easily proven. And since in most cases, governance processes are the same across all the districts within each national grouping, the system can be exported everywhere within the country.

Additionally, of course in support of this it is important that civil society activists and the media gives as much attention to this kind of system piloting and mainstreaming as it has to the one-off examples of ICT implementations and the effective application of incidences of RTI.

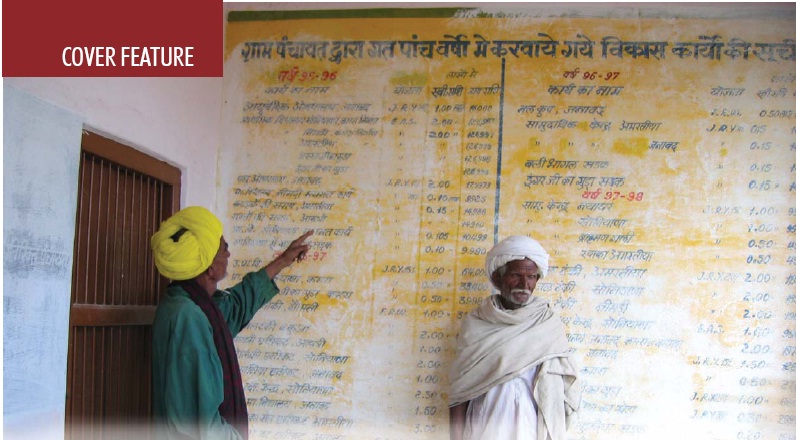

RTI and Community Informatics

The above was about the institutionalisation of the RTI at the government end, and the imperatives involved in this process. An equally important issue is that of institutionalising processes at the community level. At present, in most jurisdictions it is the urban educated population, often activists, who have used the RTI. It is relatively easy for a citybased educated pensioner, for instance, who is used to official processes, to undertake an RTI action. But the vast majority of the population in developing countries, mainly rural, poor and otherwise disadvantaged, i.e. those who are most excluded by the existing processes of governance, are mostly absent from the RTI picture. It is important for these elements of the population and these communities that RTI processes are embed and institutionalised into appropriate local community informatics systems.

ICT-enabled processes are also needed in communities for RTI to be operationalised to its real potential and this goes beyond the obvious observation that if most public information is put on the Internet, people will need to have the Internet available in order to access it. Community informatics implies making use of ICTs to develop new empowering systems of information and communication processes at the community level. RTI is emerging at a time when access to information has taken on a new meaning and set of possibilities due to the spread of ICTs.

Village tele- (or information or knowledge) centres are being promoted as a new institutional form in many Developing Country contexts including rural India, to become local nodes supporting a variety of existing and new institutional processes including in the area of small business development, social organization, governance, and education and health services.

An ideal community informatics implementation will however, not simply be a one-way flow of information into the village community. Equally it will provide opportunities for peer-to-peer as well as bottom-up information flows as for example, community built databases which could complement and authenticate official records or provide alternatives to existing records which may be faulty or otherwise misleading.

The development of such community-generated data has been one of the most important ways in which truly “effective uses” of the RTI provisions have been implemented by disadvantaged communities. Two RTI activist groups in India, Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan and Parivartan, have collected their own data – MKSS about daily wage payments in public works activities, and Parivartan about the Public (Food) Distribution System (PDS) – and have challenged official records in these important areas. These activities have led to significant community empowering outcomes. These examples demonstrate the value of further systematizing such processes and of placing RTI in the context of the development of community informatics applications specific to each community.

In a mature community informatics context, the information collection activity need not only be oppositional and confrontational. Community processes in telecentres can also support the efficiency and effectiveness of public service delivery. One instance of this is in the IT for Change Mahiti Manthana project in villages in Mysore where women self help groups ‘own’ such telecentres. It is anticipated that the telecentre or Village Information Centre(VIC) operators will collect information monthly on the health intervention needs of pregnant women and young children in the village. This information will be passed on to public health service providers, so that they can plan their visits accordingly. This information will also be copied to all higher officials. This will save the visiting health staff the need to visit every house to find out which households require their services during a particular visit. The VIC operator, at a later time, will collect data on actual interventions made by the health system, and this information will be available to be compared with the earlier set, which identified the needs.

Ultimately all of this information will be routinely sent to all levels of the health service machinery. However, it may not be sufficient to trust that there will be an automatic intervention from the higher levels even when information concerning gaps in service provision is routinely and systematically made available. The same VIC which will build the community information base will also act as a RTI facilitation centre helping community members to obtain access to official information concerning health interventions that may be mentioned in the official records but may not have actually been performed or which have been made but which have not been entered into the official record. In this way providing access and the means for effective use of health information at the community level will enable a people’s audit of the health system and its overall accountability and transparency as well as ensuring that the field workers will be kept on their toes because they will know that information is flowing to the higher levels.

It should be noted that a “Right to Information” is meaningless and particularly for those with little means without a consequent means for enabling the “effective use” of this information

Such an integrated community informatics approach to village level information gathering and management can also be seen as a viable alternative to the currently cumbersome and often inaccurate manual public health data filing system which of course, is a major contributor to the system’s overall inefficiency.

Similar information access and communication processes can be established in other areas such as the management and delivery of public works (including workforce enrolment and wage payments), government revenues and expenditures, taxation, education services, agriculture extension among others. However, as pointed out earlier, it is essential that these processes are systematized and institutionalised, so that they both contribute to the continuing upgrading of the machinery of government at the same time as they are increasing the transparency and accountability of governmental operations. It is only when robust information and communication systems are set up, and are sufficiently institutionalised at the community end, that real and sustained benefits from RTI will begin to flow.

RTI, ICTs and Good Governance

The formalisation of a Right to Information carries with it the potential of far-reaching transformation of Indian governance, but for this purpose the RTI law needs to be exploited systematically. It is important also to recognize that the opportunities presented by a formalized RTI, as for example, the Indian RTI Act, can only be fully operationalised and routinised through the development and implementation of appropriate information systems and the automation of government operations. Incorporating new processes built around the appropriate and effective use of the new ICTs, both at the government end and at the community end, is absolutely essential for this purpose and overall for achieving “good governance” at both the local and the national levels.

The fears that the bureaucracy has expressed, and attempts to dilute the law, and stall its implementation in various ways, only serves to show the potential of the RTI law. The Indian RTI law is widely accepted to be very progressive, and carries the means to build a popular movement for re-claiming and reenabling the institutions of citizen based governance and real democracy.

Be a part of Elets Collaborative Initiatives. Join Us for Upcoming Events and explore business opportunities. Like us on Facebook , connect with us on LinkedIn and follow us on Twitter, Instagram.