Urban India till a few years ago, was oblivious to facing the issues of climate change because most urban residents tend to believe that they live in a cocoon and no harm can befall them. For me personally, the first noticeable effects of the changing climate became evident, when there were fog banks covering the entire north of India, and Delhi plus a few large urban areas were relatively untouched by these fog banks, writes Vaishali Nandan, Project Head – Climate Smart Cities, GIZ.

Over a period of time, the effects of heat waves, urban floods, cyclones, droughts, etc. have been documented and some of these are also attributed to the effects of climate change. Many times, however, these issues can also be attributed to man-made or mis- management, for example, delayed opening of sluice gates of the Idukki dam coupled with landslides resulting from deforestation in the Western ghats (Kerala floods 2018).

Fig 1: The checklist helped prevent illegal C&D waste dumping by identifying 17 designated sites for C&D waste disposal

Urban flooding is one example where rampant encroachments in the natural path of the flow of water lead to regular flooding and subsequent losses for both the municipality and city residents. Sometimes unplanned/ planned structures/ buildings come up in areas ignoring the area plans/ local knowledge. One such example is the Kochi airport, built on previously marshy land resulting in closure for a few days every year due to flooding. Chennai floods of 2017 can also be attributed to similar encroachments, with high rise buildings being built in previously marshy areas. Or filling of Construction & Demolition (C&D) waste in low lying areas or dumping of garbage in open drains, where even cities that are used to regular heavy rains, get flooded (Mumbai, Gorakhpur). Even, small actions by the city/ residents like paving of the inner-city roads and footpaths with tarmac and/or bricks and not leaving any recharge areas, result in a rapid flow of water along the natural slopes, thus contributing to urban flooding.

Some things attributed to climate change are the increase in intensity of rains in a shorter duration with or without varying frequency of rains, thereby contributing to the urban flooding phenomenon. Similar is the case with heat waves that are increasing in intensity causing loss of life and productivity.

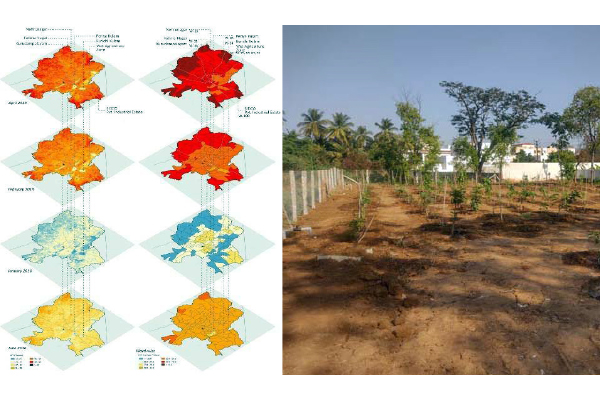

Heat waves, especially in the northern plains, are getting more frequent, with temperatures nearing 50 degrees Celsius in many parts of the northern plains. This year, temperatures in Delhi have already crossed the 100-year high in April. The increase can be linked to areas of dense buildings where air movement is restricted, large scale built-up (buildings, roads), decrease in the tree density, large scale usage of air conditioning, etc. A heat island mapping analysis conducted by GIZ for the cities of Kochi, Coimbatore and Bhubaneswar clearly showed the increasing temperatures in the cities in the past 10 years, which has mainly resulted from reducing blue-green infrastructure and an increase in built-up areas.

Also Read | Using Urban Management to Increase Urban Green Cover – A case of Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu

So, the question is, how can we provide adequate direction to prevent or correct these actions on the ground? One can contend that there is a need to re-look at current practices in cities. But where does one start?

A good place to start is the bye-laws governing the city administration. However, without the direction from the national level/ state level or proven evidence with application on the ground, changing the existing system is difficult.

Keeping this in mind, and as a part of the Climate Smart Cities project funded by the German Federal Ministry of Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety, and Consumer Protection (BMUV) under the International Climate Initiative (IKI) and implemented jointly with the Ministry of Housing & Urban Affairs (MoHUA), Government of India and GIZ. GIZ is supporting the Smart Cities Mission at the national level and working in the 3 cities of Bhubaneswar, Coimbatore and Kochi on implementing concepts of integrated and climate-friendly urban development. The National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik (DIFU), and TU Berlin, are implementing partners to GIZ on the project.

The subject of climate change in the cities is being addressed via sectors, as this is what the cities understand and are comfortable implementing. Thus, the areas of implementation on the ground included subjects like management of stormwater, construction and demolition (C&D) waste management, solid waste management, urban green planning, and green buildings, depending on the choice of the city.

All cities have introduced some changes in their policy framework, for example, Coimbatore has launched an ‘Adoption policy for open space reserved (OSR) areas’ to convert OSRs into mini forests using the Miyawaki method and through community and public-private initiatives (34 MoUs have been signed and 100 planned); C&D waste dumpsites were identified based on an environmental checklist and dumping in low-lying areas was prevented (17 sites); a local Climate Alliance has also been formed.

Similarly, in Bhubaneswar, C&D waste management bye-laws are under the notification, while in Kochi a checklist for green buildings was launched by the Mayor. The sponge city concept is under development for the Nayapalli area in Bhubaneswar, with rainwater harvesting, perforated pavements, etc. being proposed as measures for urban flood prevention.

However, the interconnectedness of all these sectors is far from being realised and they continue to function in silos. The fact that all areas are elements of the larger integrated urban planning puzzle is far from being realised by the city governments. Attempts were made by the project to integrate some aspects in the master planning process in the cities, however, they did not progress far.

Figure2: Urban Heat Island mapping analysis and Open Space Reservation area being converted into a Miyawaki plantation, Coimbatore

At the national level, steps towards an integrated approach have been initiated in the form of the Climate Smart Cities Assessment Framework (CSCAF) exercise initiated by the Smart Cities Mission of the Government of India, with the support of GIZ and NIUA. CSCAF clubs 12+ subjects (waste supply, wastewater, stormwater, energy, green buildings, waste management, mobility, air quality, urban planning, biodiversity and green cover) into 5 sectors and 28 progressive indicators for ease of work. The CSCAF has also been integrated in the National Mission on Sustainable Habitat, however, these can be considered only baby steps towards integrated urban development for the silos to be broken.

Training and capacity building are other forms of implementation support. It is hoped that policy changes strengthened by learnings from the ground-level implementation will provide the Training institutes with the necessary tools and champions for further scale-up. State or regional training institutes must be empowered to train as well as deliver in local languages for sustainability.

Also Read | SDG 11 & Indian Cities

We should address these gaps in planning and implementation should be addressed through several means, namely-

i) Stronger ownership from the urban planning fraternity to climate proof the Master Plans, area development plans, etc., and move towards an integrated urban planning approach.

ii) City managers need to be trained to look at the city as a whole and not in parts.

iii) Need for community participation to act locally.

It is hoped that by doing some of the above, we will move one step closer to adapting to the vagaries of climate change.

Be a part of Elets Collaborative Initiatives. Join Us for Upcoming Events and explore business opportunities. Like us on Facebook , connect with us on LinkedIn and follow us on Twitter, Instagram.