Central and State Government agencies in India have for decades, attempted to ensure an adequate house to the nation’s poor. Schemes rolled out have included housing subsidisation programmes, provision of basic infrastructure, incentivising private sector participation, dedicated housing finance and rental housing. The gap between the supply and demand of adequate homes however has only widened over time, pushing the target ‘SDG 11.1: Safe and Affordable Housing (for all)’ further ahead, writes Rejeet Mathews, Director, Urban Development, World Resources Institute (WRI) India.

In 2012, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) estimated the national urban housing shortage to be 18.78 million units, of which obsolescent, kacha and congested housing was 97 per cent. This indicated that the larger problem was that of inadequate housing stock and not that of homelessness. It also reported that 96 per cent of this shortage of adequate homes was in the economically weaker sections (EWS) and lower-income groups (LIG).

Government sub-schemes such as Affordable Housing in Partnership – AHP, provide a new house in a new location, which is often not desirable due to increased distances from existing housing locations and jobs. Some schemes require the beneficiary to have ownership of the land such as Beneficiary Led Construction which indicates that the recipients are financially better off than the ‘most in need’. Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) in affordable housing have not picked up momentum due to the land being expensive thus yielding low-profit margins while slum redevelopment remains a complex process.

Even when hard-won milestones such as land procurement and housing construction have been overcome, centrally sponsored housing schemes have unanticipated levels of vacancy. In responses made to questions raised in Parliament on the matter, vacancy levels of 23 per cent (2,38,448 houses) in 2016 and 17 per cent (2,00,677 houses) in 2017 of total constructed houses were reported. Reasons for vacancy were stated as the reluctance of slum dwellers/beneficiaries to relocate, and lack of basic infrastructure and livelihood opportunities at these locations.

Gaining a ground-up perspective is critical to solving the affordable housing conundrum in India. A round of preliminary interviews conducted by WRI India with short and long-term migrants working in the informal sector in Delhi-NCR showed that workers opted to live in basic set-ups to save costs while being close to their community networks and workplaces. Cumulative expenses of comfort and living quality were kept to a minimum to maximise savings to send back to extended families and even children living in the village. Title rights to houses they occupied were a higher priority than better infrastructure access, which they themselves were willing to invest in if they had security of tenure. Workers preferred housing at a 2 to 5 km distance from their workplaces to avoid high transportation costs and prioritise being rooted in community networks to help tap new jobs.

Issues, concerns and needs identification discussion at BSS Camp, Rajokri, Delhi

It is evident that making land available at the right location and at the right cost for affordable housing is at the heart of achieving SDG 11. The price of land in Indian metropolitan cities is high and any real estate built on it becomes highly inaccessible to most within city limits. The following are ways in which successes have been achieved in the Indian context itself, by utilising the land as a resource to realize affordable housing and related urban infrastructure targets that need to be scaled up for India:

Land & Housing Reservation: With the intent to provide an equitable supply of land, shelter and services at affordable prices to all sections of the society, the National Urban Housing and Habitat Policy 2007 recommends reserving 10 to 15 per cent of the land in every new public/private housing project or 20 to 25 per cent Floor Area Ratio (FAR) whichever is greater for EWS/LIG housing through appropriate legal stipulations and spatial incentives. These policies have been adopted by various state governments such as Maharashtra and Karnataka. Further, a suitable percentage of land developed by the public sector is to be provided at institutional rates to organisations like Cooperative Group Housing Societies, to provide housing to their members on a no-profit no-loss basis.

Intensive Utilisation of Land: The Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana–Urban (PMAY-U) has encouraged States and UTs to provide an additional built-up area (FAR/TDR) and related density norms for slum redevelopment and low-cost housing where required. Within the Affordable Housing in Partnership (AHP) sub-scheme, private entities are granted higher FAR on land parcels owned by them in exchange for making available a portion of that land or other land to the government for affordable housing. Private sector builders will also be allowed to create high-end housing for which there is a profitable market under the condition that they provide affordable housing.

Unlocking Underutilized Government Owned Land: The Union Budget 2021-2022 gave a push to monetise underutilised assets. PMAY-U encourages land owned by various central and state government departments and agencies which are in excess of their requirements to be effectively pooled and brought under affordable housing. Redevelopment projects and increasing the supply of land through the process of change in land use is also encouraged.

Land Tenure Rights: NSSO estimates suggest that approximately half of the urban households in India are landless. Landlessness and insecure tenures in slums do not encourage residents to invest in home upgradation and connecting basic infrastructure and are a fundamental driver of poverty. To change the status quo, the Government of Odisha has passed legislation to assign land rights to eligible urban slum dwellers for redevelopment, rehabilitation and upgradation in Notified Area Council (NAC) areas and Municipalities across the state under the ambitious JAGA Mission.

Servicing existing low-income housing with trunk infrastructure: Providing new, tenure secure houses for all is financially unviable for government agencies but extending trunk infrastructure will greatly improve the physical quality of life in informal settlements. The Government of Delhi changed legislation to allow MLA LAD funds to be spent in slum settlements which resulted in water supply, sanitation and road improvement. The Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board has introduced 662 Jan Suvidha complexes in slums containing community toilets and baths which are free of user charges. Other basic amenities such as drinking water points, street lighting, ghaats for clothes washing have also been provided.

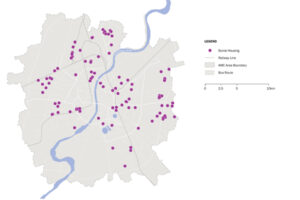

Well distributed locations of social housing in Ahmedabad

WRI – WRR Case Study

Land for Sites and Services: Small sites are provided with basic services to low-income households, giving them the security of tenure for incremental self-construction of a house. While the sites and services schemes no longer form a part of central government outlays, research from the World Bank (2017) indicates that providing serviced plots (ranging in size from small to big) in expanding peripheries has created well planned mixed-income neighbourhoods with access to amenities and other good planning outcomes almost 2 decades later and must be viewed in this time horizon.

Alternative Mechanisms to Acquire, Plan and Service Land for Affordable Housing: The Town Planning Scheme (TPS) employs a land readjustment mechanism that brings together a group of landowners who pool their land parcels for development. After deducting the area for infrastructure and social amenities, including affordable housing, the government reconstitutes the remaining land into regularly shaped plots and distributes it back to the original owners. Infrastructure is provided by the local government agencies; landowners benefit from improved services and this increases the value of their land. Ahmedabad has used this technique to make lands available for affordable housing which resulted in over 80,000 dwelling units getting constructed under various affordable housing schemes as per a WRI study. These schemes are well distributed spatially across the city instead of being concentrated in the city’s periphery, as is common in many parts of the world.

India’s urbanisation trajectory remains strong and hence requires policies, plans, regulations and mechanisms that can prevent the occurrence of inadequately serviced and unplanned urban expansion as well as under-provisioned inner-city areas. Land needs to be acquired, planned, and serviced with adequate infrastructure, social amenities, and affordable housing for our cities to thrive.

Be a part of Elets Collaborative Initiatives. Join Us for Upcoming Events and explore business opportunities. Like us on Facebook , connect with us on LinkedIn and follow us on Twitter, Instagram.