India, the second-fastest-growing major economy and the country with the largest population in the world, is on the brink of a water crisis. To meet the increasing demands of its growing population, the country is undergoing accelerated development, which has placed tremendous pressure on its unique ecosystems, particularly freshwater systems. Urban areas play a significant role in India’s landscape and economy. The country is currently experiencing rapid urban growth, with the urban population projected to increase by 590 million and the contribution of cities to the GDP expected to rise by 75% by 2030 (MoHUA, 2021).

The expansion of urban sprawl, unplanned development, increased grey infrastructure, and land resource demands further exacerbate the pressure on freshwater ecosystems, their health, and services. Urban areas, characterised by high population density, continue to experience growing demands for consumption due to rural-to-urban migration, while the ecological carrying capacity of cities remains constant. In order to meet these increasing demands, cities rely on water, food, and energy supply from other parts of the landscape, such as watersheds or upstream catchment areas, which has implications for ecosystems beyond the city limits. Therefore, urban areas and cities have a crucial role to play in impacting and managing the health of freshwater ecosystems at local and watershed scales.

Within cities, the hydrological cycle, landscape, catchment area drainage, wastewater systems, and channel geomorphology are highly disrupted. These disruptions impose constant stress on dependent ecological components, resulting in a reduction in urban tree cover and green belts surrounding bodies of water, a decline in groundwater levels and recharge, an increase in summer temperatures (urban heat island effect), the presence of urban stream syndrome¹, degraded soil quality, and an increased risk of floods and droughts (Krauze et al., 2019). Ultimately, these disturbances lead to an altered ecosystem structure and functioning, causing the degradation of urban wetlands, rivers, shorelines, and other aquatic ecosystems, as well as a loss of biodiversity.

Given the interconnected nature of freshwater ecosystems, localised impacts of urbanisation can affect watershed hydrology, structure, function, and services. For instance, increasing impervious surface areas result in elevated water yield in watersheds through increased direct runoff (Li et al., 2020). Increased runoff is also highly effective at eroding available sediment sources, thereby increasing siltation in water (Russell et al., 2017). Highly concentrated effluents and sewage also get transported downstream, impacting the water quality of river and groundwater systems. Multiple urban centres within watersheds can lead to cumulative or magnified impacts on freshwater ecosystems within the watershed.

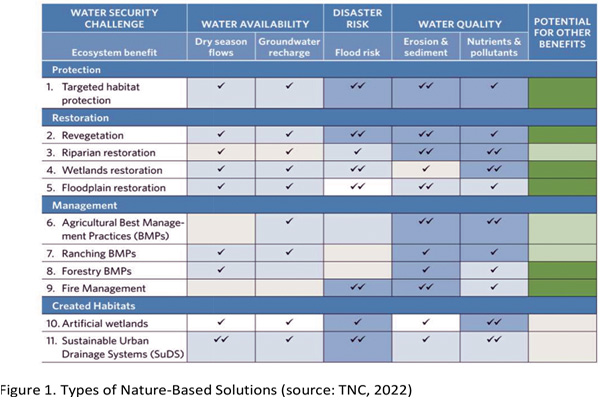

Urban areas heavily depend on grey infrastructure for the storage and distribution of water resources. Grey infrastructure is resource-intensive and has a long-term negative impact on several components of the landscape and freshwater ecosystems in a city. Therefore, Nature-based solutions (NBS) have been recognized as one of the most comprehensive approaches for developing resilient urban landscapes. NBS incorporates the natural environment and mimics or works in tandem with natural processes. It is defined as “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems that effectively and adaptively address societal challenges while simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits” (IUCN). NBSs can be of four types (Eggermont et al., 2015; Pontee et al., 2016; Figure 1):

(i) Fully natural solutions consisting of no or minimal intervention in ecosystems

(ii) Managed natural solutions consisting of interventions for sustainability and multi- functionality of managed ecosystems

(iii) Hybrid solutions consisting of managing ecosystems in very intrusive ways such as interventions that combine structural engineering with natural features

(iv) Environment friendly structural engineering consisting of creation of new ecosystems

NBS are increasingly being used in urban spaces to enhance the quality of life of the urban population and address water issues (UN Environment-DHI, 2018). However, a recent study of 4,000 cities found that 80% of them could improve water quality and reduce water treatment costs by working closer to the source with water users in the catchment to improve land and forest management practices (Abell et al., 2017).

A key feature of NBS is that they tend to deliver groups of ecosystem benefits and services, usually offering multiple water-related benefits and often helping to address water quantity, quality, and risks simultaneously (WWAP, 2018). Hence, there is a huge potential for NBS application in India to meet the targets/goals defined for the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs; target 6.6), the UN Decade of Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030), and the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (30 by 30). At The Nature Conservancy, we are working to plan and implement NBS at various scales.

Basin/Watershed

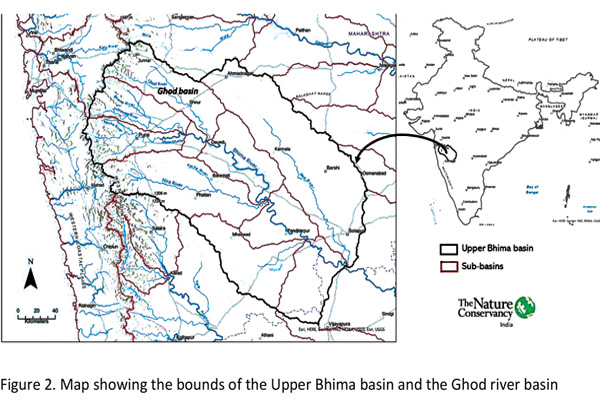

- Conservation planning in Upper Bhima basin: Conservation planning focuses on using a structured, science-based framework to deliver actions that achieve conservation goals aiming at long-term persistence of ecosystems and the efficient use of natural resources. This approach is being used to plan for restoring freshwater ecosystem health in the Upper Bhima basin.

- Ghod river water fund: Water funds are financial and governance mechanism- that bring together all the water users to invest in and implement NBS for source water protection/ conservation. Water Funds are implemented by The Nature Conservancy in 13 countries.

Cityscape

- Chennai Greenprint: Green Printing blends landscape/ watershed level conservation, urban planning and development process to identify trade-offs between development plans and conservation outcomes. Embedding Greenprint into the city’s master plan will help shape the city’s sustainable growth proactively.

Water body

- Sembakkam Lake restoration in Chennai: The project used NBS(such as reed beds is planned for treating sewage water entering the lake) to restore the lake ecosystem health.

Efforts to mainstream NBS in Indian cities are currently underway (NIUA- WRI; https://www.nbs4india.org/) which can also be used to highlight the importance of implementing NBS for freshwater ecosystems conservation. Though such efforts are crucial, there is an urgent need to solve the challenges of bringing multiple stakeholders together to agree on integrated solutions and developing innovative financing mechanisms to implement such solutions successfully on a wider scale to see perceptible impacts.

Views expressed by:

Roshni Arora, Gargi Joshi, Girija Godbole, Alpana jain

Be a part of Elets Collaborative Initiatives. Join Us for Upcoming Events and explore business opportunities. Like us on Facebook , connect with us on LinkedIn and follow us on Twitter, Instagram.

"Exciting news! Elets technomedia is now on WhatsApp Channels Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest insights!" Click here!